Why Good Product Development Needs a Critical Design Review

Introduction

Good product development follows clear principles. One of the most important is the critical design review (CDR)—an unbiased process that challenges complexity and ensures designs meet real-world constraints.

Years ago, I worked on a project for Hewlett-Packard (HP) that highlighted this principle. The goal was ambitious: design a machine that could manufacture paperback books on demand, right inside an office.

The Project: An On-Demand Book Machine

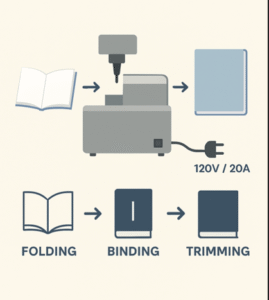

The idea was simple in concept but complex in execution. The machine needed to:

-

Fold and assemble booklets

-

Glue them to a spine

-

Attach and laminate covers

-

Trim pages for a professional finish

The business case was strong: eliminate printing delays and reduce the cost of shipping books. But turning the concept into a practical machine required careful engineering.

office-based book binding machine

The Problem With Trimming Pages

One major challenge was the uneven edges caused by folded pages. If you fold five sheets of paper, the inner sheets extend farther than the outer ones, creating a V-shape.

Our first idea was to trim each page individually before binding. But this introduced serious problems:

-

Required huge processing power to track each sheet

-

Increased electrical load, exceeding commercial limits

-

Added complexity with little payoff

Power and Processing Constraints

The machine needed to run on 120 VAC power at no more than 20 amps, without requiring custom wiring. Adding more power or specialized processors would have raised costs and limited market adoption.

Early tests with an existing microprocessor showed it struggled to manage folding, gluing, stapling, and trimming simultaneously.

The Simplification Breakthrough

A critical design review forced us to rethink. Instead of trimming each page individually, we could bind first, then perform a single trim operation—the same method used in mass-market paperback production.

-

✅ Reduced processor load

-

✅ Lowered power requirements

-

✅ Allowed use of affordable components

-

✅ Preserved commercial appeal

The tradeoff was slightly less smooth edges, but the design became more efficient and realistic.

Lessons in Product Development

This project reinforced the KIS principle—Keep It Simple, and complicate only when necessary.

Key lessons:

-

Simplify steps wherever possible

-

Design within power and cost constraints

-

Choose components that balance performance and affordability

-

Ensure manufacturability for commercial success

The Human Factor

HP’s internal incentive program rewarded employees with cash bonuses for ideas that reached production. The project manager was the original idea champion, which added momentum.

But due to management issues at HP, the project was eventually canceled. A few years later, another company successfully introduced a similar book-on-demand machine to the market.

Conclusion

The experience proved a valuable lesson: critical design review is essential for successful product development.

CDR forces teams to challenge complexity, validate assumptions, and design solutions that balance performance with real-world constraints.

In product development, the best solution isn’t always the most perfect one—it’s the one that works reliably, affordably, and at scale.

Norman T. Neher, P.E.

Analytical Engineering Services, Inc.

Elko New Market, MN

www.aesmn.org